A Q&A with Kipp Dawson ’94: Activist, Educator, and This Year’s Hollander Lecturer

Kipp Dawson ’94, center, poses for a photo at a 1989 abortion rights march in Washington, D.C. (Kipp Dawson)

Labor. Women’s liberation. Civil rights. Vietnam.

Name a progressive American activist movement from the last 60-plus years, and there’s a good chance Kipp Dawson ’94 was there, marching, picketing, showing solidarity, or finding some other way to get involved with it.

At this year’s Barbara Stone Hollander ’60 Women’s Leadership Lecture, Dawson will talk about her history with all these movements and more. Additionally, selected items and images from her vast collection of approximately 250 T-shirts related to activist, labor, and other organizations will be on display the Susan Bergman Gurrentz ’56 Art Gallery at Shadyside Campus as part of the “Wearing the Movement” exhibition between Oct. 15 and Dec. 12.

Ahead of the lecture on Oct. 15, Pulse sat down with Dawson to talk about her history of activism, her unique stint as a Chatham student, and the years she spent working at Pittsburgh Public Schools.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Pulse: I’m interested to hear how you ended up in western Pennsylvania, because your biography says you grew up mostly in northern California.

Kipp Dawson: I was born at the tail end of World War II. My dad was still in the army. My mom had been a Rosie the Riveter. My dad was stationed in Los Angeles.

They were Jews, and they decided they needed to bring a Jewish child into the world because of the Jewish children who had been killed in the Holocaust. So, my mom gave up her factory job—although she returned to it—and volunteered to drive a Jeep for the Army, so that she could get pregnant with what turned out to be me. I was born in Los Angeles in June of 1945.

My parents didn't stay there when the war ended; they went back to the Bay Area, which is where they both had been before the war. I grew up in a housing project. It was called Codornices Village. I was there for the first 10 years of my life. It had been set up for the shipyard workers and other war workers who had come to the East Bay—the Berkeley-Oakland-Richmond area—to work in the war industry. Many of them were African Americans from the Great Migration from the South, as well as Japanese Americans who had been in internment camps during World War II.

We had our own school system. It was huge. It overlapped two cities, Berkeley and Albany. We lived on the Albany side, but it didn’t matter—when we were in the village, we were all village kids. My siblings and I grew up just assuming this is what the world is: people getting along and helping each other, people who were poor, many of whom looked different from each other.

By 1966, I was a senior in college. I was getting great grades, but I had also helped to found the Free Speech Movement at San Francisco State. But then, the Vietnam War became a big deal. I helped found the Vietnam Day Committee in Berkely, Jerry Rubin’s group. We worked together. We met in Jerry Rubin's apartment at times.

At a national conference, I was asked if I would be willing to be the West Coast executive director of the big march that was happening in New York, simultaneously in San Francisco, on April 15, 1967. I was 21 years old at that time. This was a full-time thing, and it seemed like an amazing opportunity. So, I said, “Yes, I'll do it,” and it meant dropping out without finishing college. And the last college class I took was in ’66, until Chatham, which was a few years later.

How do you end up becoming a coal miner in Pennsylvania after that?

After the big march, I was asked to go to New York City to be a part of the national organizing for the Vietnam anti-war movement. I did that, and that was exciting and marvelous, and we had more big demonstrations, and I got involved in helping raise money.

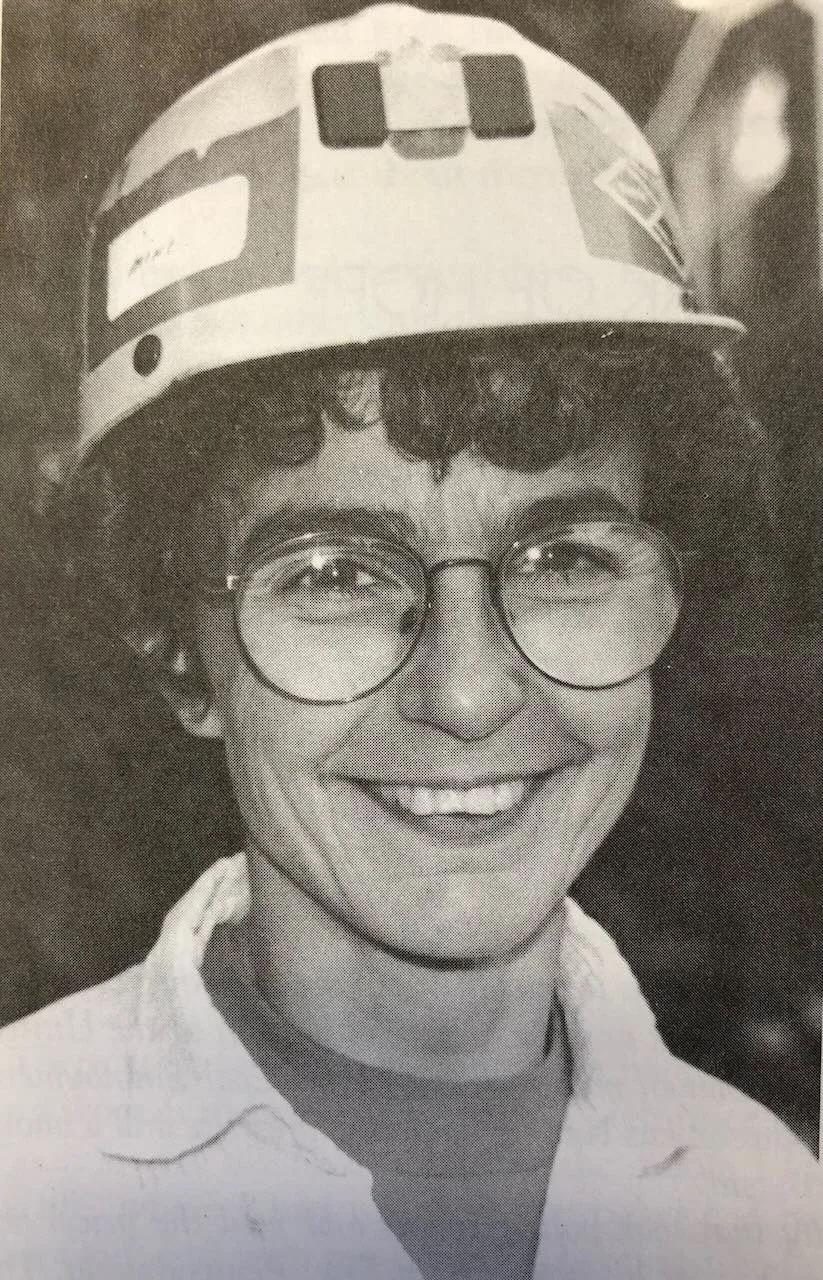

Kipp Dawson ’94 in her goal mining gear. (Marat Moore)

The way that I got to Pittsburgh was, for a while, I just worked as a printer and typesetter and graphic artist for a socialist printing company in New York. In the course of all of that, my husband and I split up, and then I came out as a lesbian, met my partner, who was involved in all these things, too. She and I were asked by the Socialist Workers Party to come here to Pittsburgh. My hope was that I could get a job in a steel mill or a coal mine like my mom and carry on what she had been doing. I was very lucky to get hired in the fall of 1979, as a coal miner, by Bethlehem Steel's coal mining division in Washington County.

Simultaneously, that meant I was a member of the United Mineworkers union, which had always been my heroes growing up, coal miners and the UMW. From 1979 until the end of ’92, that was the center of my life, working in mines. When we were on strike, we were traveling around and doing solidarity work with other miners, and going to women miners’ conventions, and doing really inspiring work, meeting all kinds of people. When British miners were on strike, we went to England in solidarity with them, and some of them came here, and we organized tours for them. My friend and I went to Australia for an international conference of miners, which included South Africans, who were still living under apartheid at that time.

That was until 1992. By that time, my current partner and I had a child, my daughter, Leah, was born in ’91. I got laid off around the same time, and at that time, the contract we were working under had a fund for people who got laid off to go back to school. I went to study at Chatham.

I will always be extraordinarily grateful to Chatham and to the Gateway Program [an undergraduate program for women over age 23 who wanted to return to college for a bachelor's degree]. Here I was, in my 40s, and I have college experience from a long time prior to that. The Gateway Program not only helped me financially, but Chatham took almost all of my credits from San Francisco State, so that it only took me a year to graduate. My goal was to become a teacher, and that's what Chatham helped me do. At that time, Chatham was a different kind of place than it is now, but that's true of everything. Everything is different than it was in ’94.

What was that year at college like for you? Like you said, Chatham was very different then than it is now.

Well, there were no men in the undergrad. There were males in the burgeoning, new graduate programs. But the all-female classes were similar to the women miners’ conferences, in that no one there was showing off for a man, and people were supportive of each other. I was thrilled to be able to have an assignment to read, because I've always been a reader. It was like Christmas, only every day.

I was a history major. Christina Michelmore was one of the highlights of my life. I took Middle East history from her, and I was stunned by her. I will mention her at my lecture on the 15th, and I will also mention Linda Rosenzweig, who's no longer alive. I became her aide as she was doing research on friendships among women in the 19th and 20th centuries. She was stunned to have a student who actually read Nation magazine.

I also worked in the library, and I ended up being a library teacher later. It was a great job, because I was surrounded by books. I really enjoyed my time at Chatham very much.

Did you have an idea of what kind of teacher you wanted to be?

Yes, I thought I did then, and I was wrong. I thought, I'm going to teach second grade. Because that's where I fell in love with learning. I knew I wanted to teach in inner city schools, like the school I grew up in. That's where I wanted to go.

I thought then that anybody who wanted to teach in middle school was crazy. And then I realized I was right—and that I was one of them! I loved, loved, loved the 13 years I spent as a middle school teacher in Pittsburgh Public Schools. I'm still in touch with kids I taught, which has been a long time ago now. A lot of them sending their kids to middle school now. I think some of them are going to be coming to the Hollander Lecture on the 15th. That makes me very happy.

From left: Catherine Evans, Kipp Dawson, and Jessie Ramey pose for a photo. (Jessie Ramey)

Can you also tell me about the art gallery exhibition of your T-shirts that ties into the lecture? That sounds pretty interesting.

As it happens, over the years, I have collected T-shirts. I don't know how they got from California to New York City to here. I really don't, but they were among the things that I took with me that were important. It also was part of the culture of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. People gave each other and wore each other's T-shirts. It's a form of solidarity that's easy to do. Since I never thought that any of the movements I was involved in became irrelevant, even afterwards, I still had them.

The University of Pittsburgh agreed to take my archives. Jessie Ramey [director of the Women’s Institute at Chatham] was one of the people who helped find and bring in the work to collect them. Catherine Evans, who is a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University, has been working with me and with Dr. Ramey on all of this stuff.

Is there anything in particular you want people to take away from your lecture?

Yes. The only reason I agreed to do this with Jessie is because I want everybody who comes in contact with any aspect of this project to see themselves as potential activists, leaders, people who can make a difference, people who have ideas that are important.

It's an anti-star approach to the world that we've never needed more than we do now. I think the idea of collectivity and camaraderie is the core. Our culture has gotten so off track with this idea that what counts is what makes you, as an individual, feel good. And forget everybody else, forget everything else.

That is the opposite of what makes humans strong and deserving of being on this planet. The things each of us do can collectively help to save and restore our beleaguered planet and build a just and verdant future for all of its children.

Learn more about the Hollander Lecture and the Chatham Women’s Institute at cwi.chatham.edu.

Read about Chatham’s history as a women’s college and its ongoing commitment to women’s leadership and gender equity at chatham.edu.