There’s Something Fishy Happening at the Field Lab

The Field Lab sits under a blue sky at Eden Hall Campus. (Annie O’Neill)

Eden Hall has a way of opening people’s minds.

Take Taylor Ginter, MAFS ’24, a graduate student who works in the Aquaculture Lab. Ginter came to Chatham University with an interest in animal agriculture, but her focus in that area broadened after delving deeper into food systems.

“I think I came in thinking more about alternative meats, like vegetarianism or like the future of fake meat,” Ginter said. “But throughout learning here, it’s kind of changed my viewpoint of being more interested in … systems that rely on previous solutions, previous knowledge that we already had, instead of trying to reinvent the wheel.”

Ginter explained this on a December morning in the Field Lab, which is located next to the Esther Barazzone Center on Eden Hall Campus. Like the EBC, the Field Lab’s systems are intertwined with those of other buildings at Eden Hall. The sanitation system has particular significance for its Aquaculture Lab, where farming things that live in water—fish, plants, and other lifeforms—is the name of the game.

Three large tanks, each typically filled with 500 gallons of water and hundreds of rainbow trout, take up the front corner of the lab. Wastewater from the tanks (as well as all wastewater from the campus’ toilets) goes to the wetlands right outside the Field Lab. Roy Weitzel, director of the aquatic laboratory, called the six-step system a hybrid between a modern wastewater facility and nature.

“Really, it’s a practical demonstration of the natural wastewater treatment that goes on in the environment for our natural ecosystems,” he said. What would normally be treated as sewage is instead able to be reused throughout the campus.

It starts in the wetlands outside the Field Lab, where wastewater is collected underground. Fecal matter, ammonia, and other waste are removed and the water is filtered with processes mimicking nature. When it’s returned to the fish tanks, oxygen is added to create the ideal conditions for the trout. Other water is returned to the campus toilets.

You’ll know this water when you see it because blue dye is added during the final steps of the treatment process in the Field Lab’s wastewater monitoring station. The colored toilet water at Eden Hall isn’t a novelty. It’s a way of making people think about something that’s often taken for granted: where water comes from and where it’s going.

One of the main issues with traditional aquaculture, Weitzel said, is how much wastewater these facilities expel back into the environment. That’s not a problem here.

“Everything that we have here is recirculating the water to use it over and over again,” he said. “That takes technology, so we have waste removal, we have filtration, we have oxygenation. We’re trying basically to take the waste out of the water and recreate the perfect conditions for the organisms that are in the tank.”

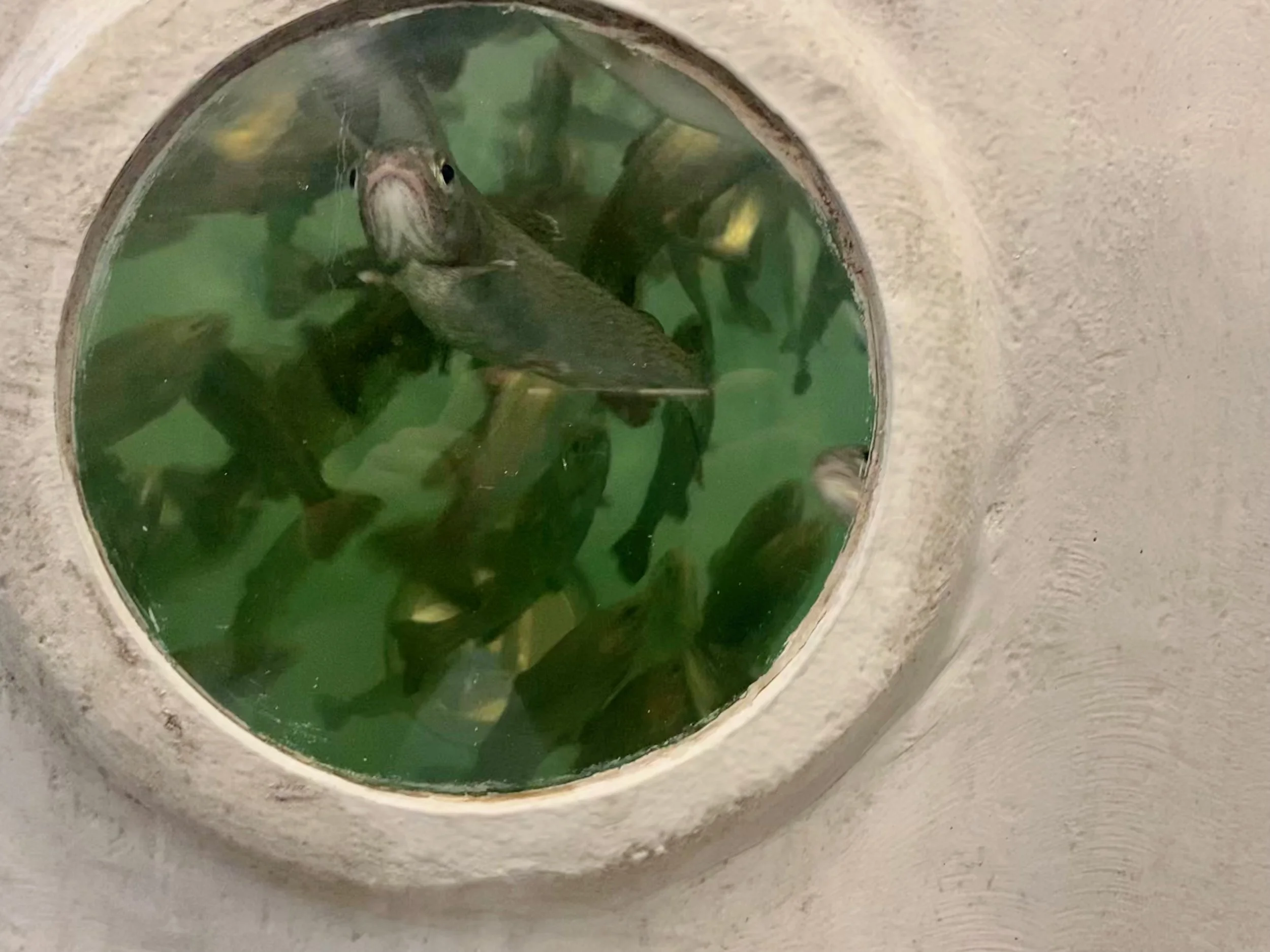

Rainbow trout swim in a 500-gallon tank located inside the Field Lab. (Mick Stinelli)

The purpose of the Field Lab itself is to be a teaching tool for students, who can utilize its systems for research and work in the laboratory classroom located next door to the Aquaculture Lab.

Marissa Ostrosky ’24, who studies environmental science, came to the lab with some experience in similar systems after an internship at the Pittsburgh Zoo & Aquarium, where she developed an interest in the technical and chemical aspects of water treatment.

Ostrosky said she wanted to keep working with these kinds of aquatic systems further when she graduates.

“Before I interned at the aquarium, I was interested in working with animals, but after working at the aquarium, I enjoyed working with [fish] specifically,” she said. Starting a career in that field can require at least some paid experience working with similar systems; her job at the Aquaculture Lab provided that.

Weitzel said it’s rare for people to have the experience necessary to work in the lab, so the University also offers an aquaculture class, where students are given their own fish tanks to learn about concepts like filtration, the nitrogen cycle, and water quality. Katy Morgan ’24, another environmental studies student who works in the lab, took that class.

“Within that class, we learned just the basics of the lab,” Morgan said. “Starting off at the smaller scale that I did in the class helped me understand the larger scale, so I got comfortable with it because of the class, honestly.”

In addition to the farmed trout, the Aquaculture Lab houses a small tank full of mealworms, a modest aquaponic system that allows growing herbs and an aquarium to share resources, and a fish pond full of algae outside.

It’s all kept Taylor Ginter thinking about life after graduation. “I can see it going a few different ways,” Ginter said. “That’s part of what I like about food systems, so much of it is incorporated in a lot of different things.

“For me, just getting to see all these different systems is really helpful,” she said.

Mick Stinelli is a writer and digital content specialist at Chatham University. His writing has previously appeared in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 90.5 WESA, and WYEP.org.