Campus Building Profile: The Libraries

The Jennie King Mellon Library “is situated to leave one with the impression that it is the most important building on campus,” the Alumnae Recorder wrote in 1973.

This is the second story in a series exploring and celebrating the history of the iconic buildings on Chatham’s campus.

The Jennie King Mellon Library, with its precast concrete so different from the red brick buildings that surround it, looks almost like it was lifted from the brutalist section of some European city and dropped squarely on Murray Hill in Shadyside.

Built in 1973 and named after the wife of Richard B. Mellon (she graduated in 1887 from what was then known as the Pennsylvania Female College), it was funded by millions of dollars that were donated to the Centennial Fund, which marked the college’s first 100 years of existence in 1969.

But before the JKM became the centerpiece of upper campus, the James Laughlin Memorial Library – the same building that now houses the Laughlin Music Center – was Chatham’s first full library.

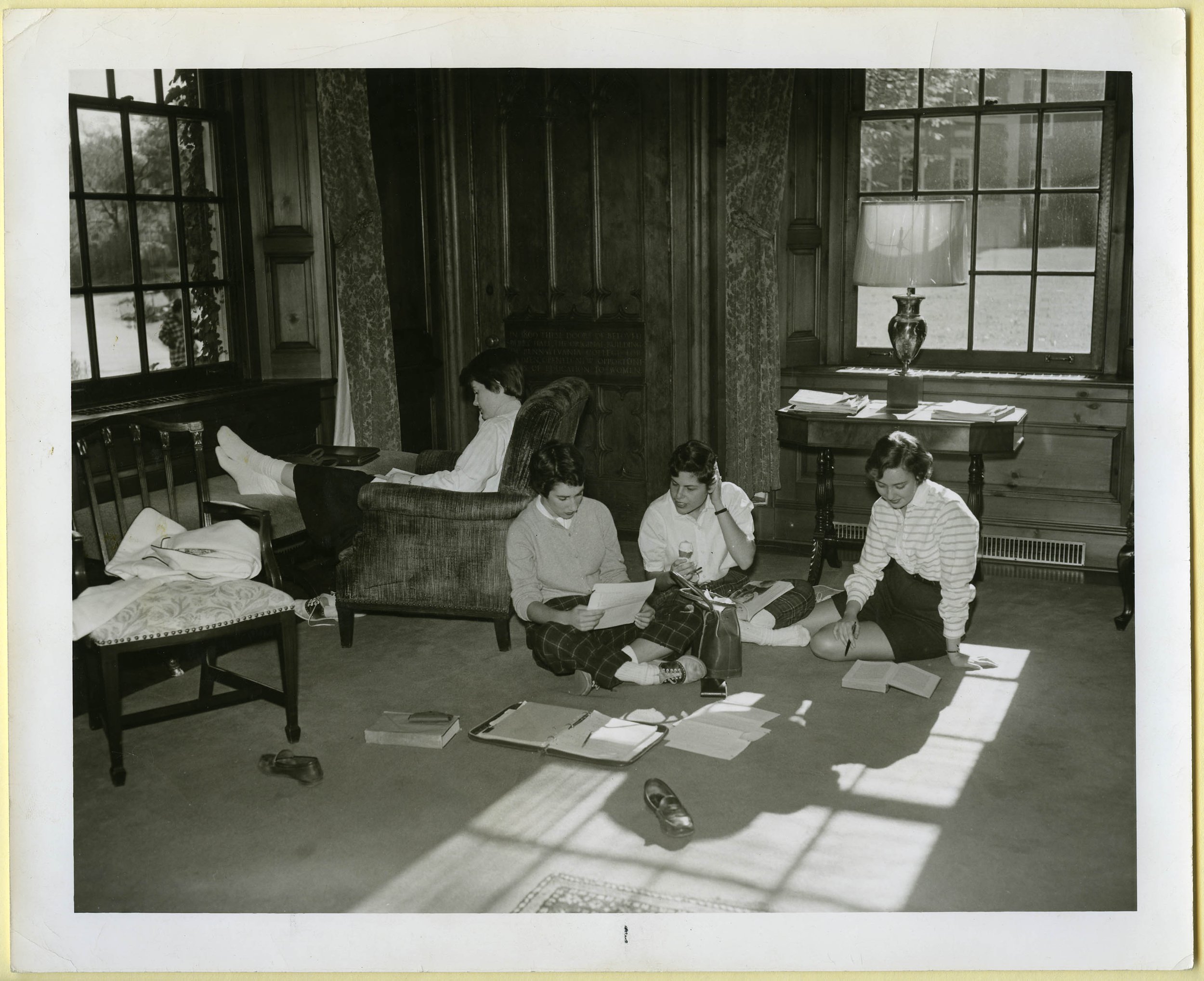

Lovely, darling, “swelegant”

(Chatham University Archives and Special Collections)

Increased enrollment and demand for on-campus housing following the first World War prompted the Board of Trustees to hire E. P. Mellon and W.L. Smith to survey the campus and options for expansion, according to University archivist Molly Tighe.

“There was a lot of building happening from the late 1920s and culminating in the building of the Laughlin Library,” Tighe said.

The Laughlin Memorial Library opened in 1931. Before then, the books were stored in a library tucked away in the gigantic, original Berry Hall.

The new library was named after James Laughlin, who migrated to the United States from County Down, Ireland, after his mother died in 1814. After serving as president of Fifth Avenue Savings Bond, he formed the Jones and Laughlin Steel Company (commonly known as J&L Steel) with Benjamin F. Jones.

He was one of the founders of Chatham University and the first president of its board of trustees. Three of his great-granddaughters attended the groundbreaking ceremony for the library.

“The library building was built with the idea of a beautiful building rather than an efficient one,” wrote Harriet D. McCarty, who served as a campus librarian from 1926-42. “The architect had never built a library and had no contact with authorities on library building.”

The building’s beauty is evident even today; students and others going to Laughlin still enter through the vestibule that leads to what would have been a circulation room lined with shelves of books.

Student attitudes toward the library were warm upon its construction, especially considering the dire economic conditions of the Great Depression.

An editorial in a 1932 edition of the student newspaper “The Arrow” says reactions to the building ranged from “lovely” to “darling” to “swelegant.”

“The wonder of having such a building in this year of depression makes the library doubly valuable,” the editorial reads.

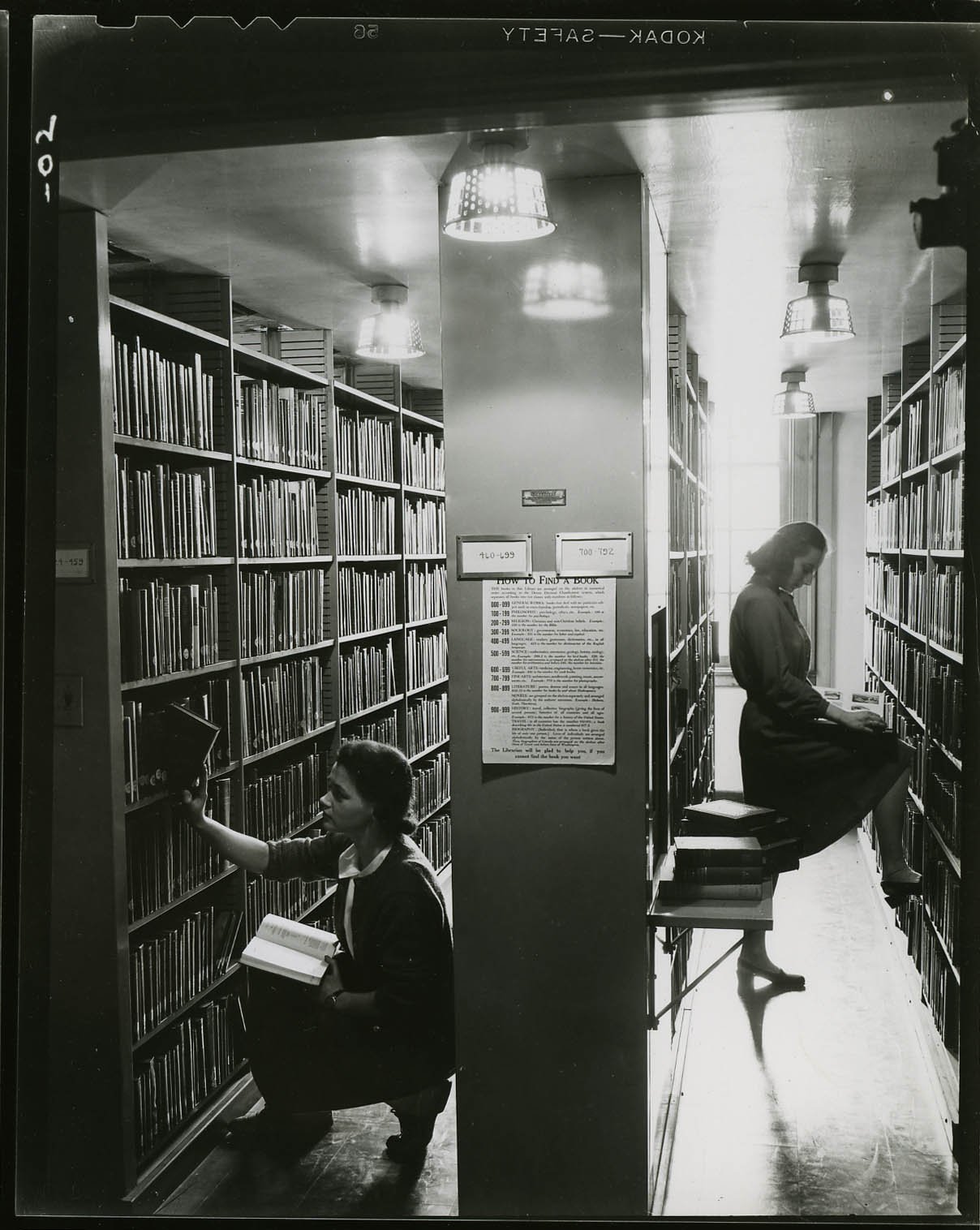

But by the 1960s, those attitudes had begun to change, at least among students writing at “The Arrow.” A 1967 editorial in the student newspaper eviscerates the library, calling its conditions “blatantly inadequate” and “a sad state of affairs.”

The reasons: too many students (enrollment increased by 300 since 1931) and too many books (15,000 volumes more than the library could hold in its stacks).

“Chatham cannot wait ten or even five more years for a new library unless some satisfactory substitute can be found in the meantime,” the article read. Those pleas would have to wait six years.

Brutal on the outside, groovy on the inside

(Chatham University Archives and Special Collections)

Why the JKM’s architectural style is so jarringly different from other buildings on campus is hard to figure out, even when looking through the University’s archival materials related to its construction. The archives contain more reports and memos about the accommodations that needed to be made inside the library than how the exterior should look.

Chatham: A Transformational University says the design may have come from “a few faculty members who wanted forward-looking contemporary architecture” rather than going with the Georgian style again. Who those faculty members were is not made clear.

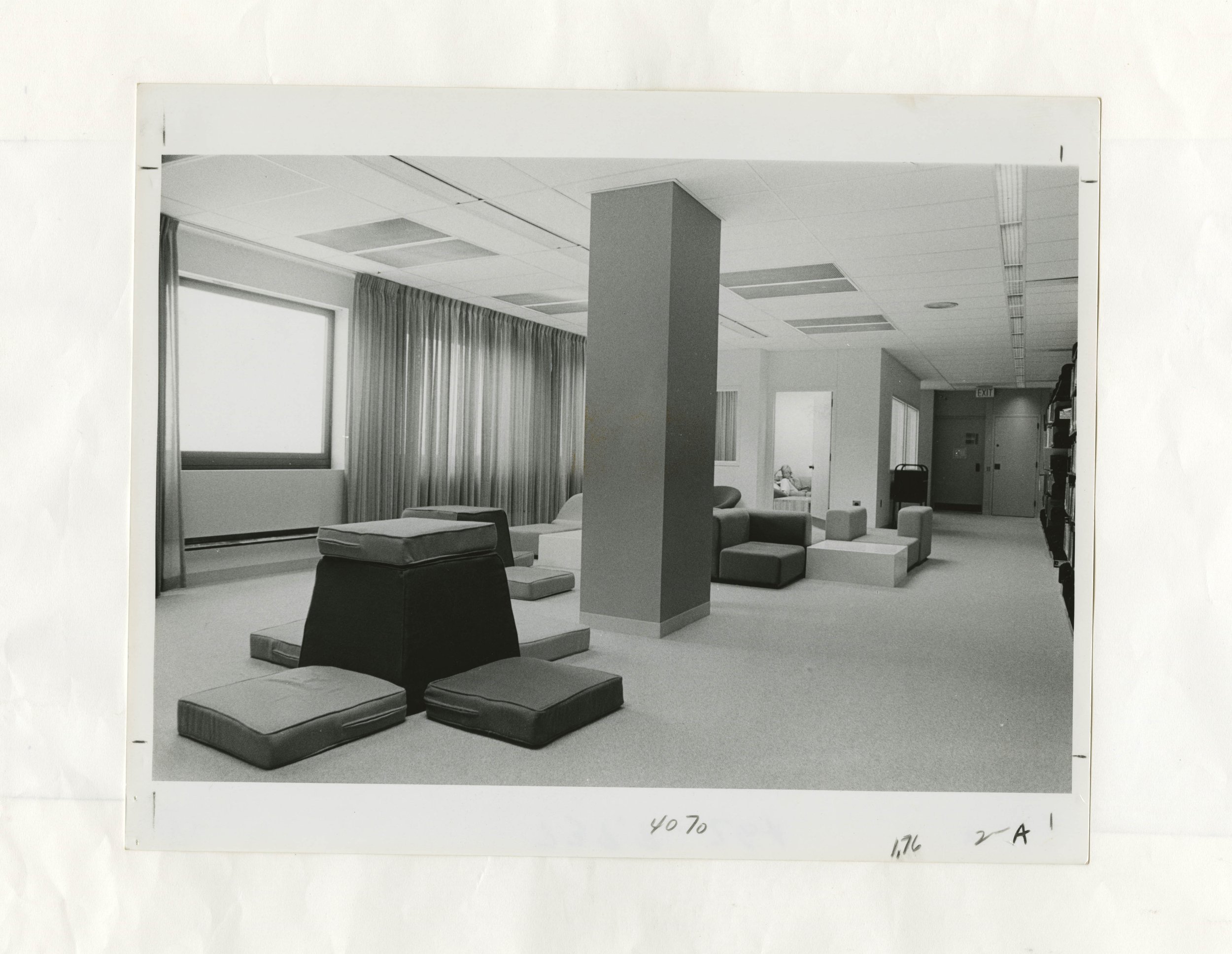

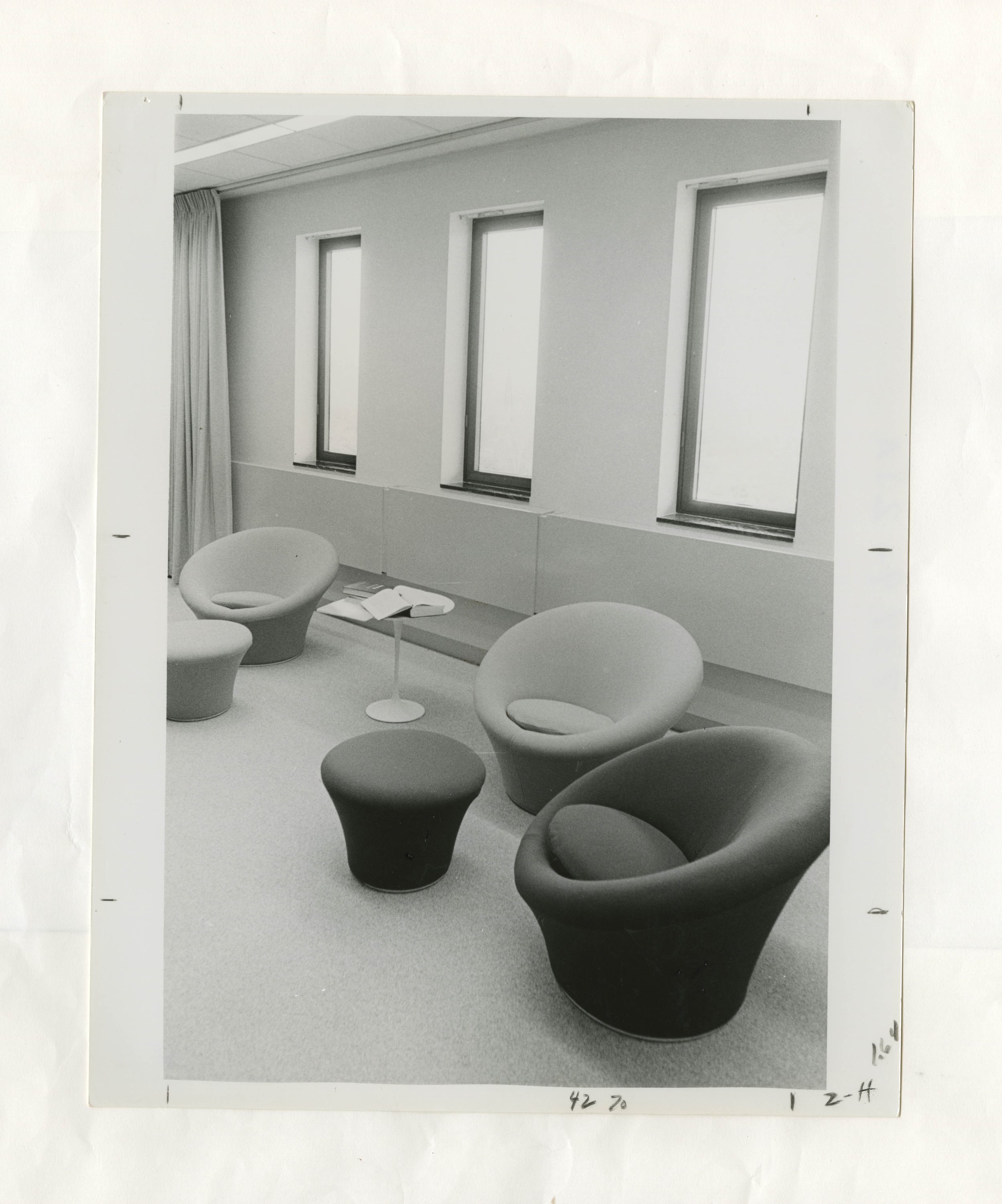

(Chatham University Archives and Special Collections)

A 1968 memorandum titled “A Statement by the Faculty Members of the Library Facilities Committee” suggests that the “new” library should contain soundproof study rooms, microfilm readers, a map room, and smoking lounges on the second and third floors.

“These lounges, or reading rooms, should be made as comfortable, attractive and inviting as financial means permit, with wood paneled walls, leather armchairs, period furniture (not necessarily authentic) and, perhaps, fireplace,” the memo reads.

Ah— the ’70s!

What is clear from reviewing the archives is that the University carefully considered what role the new library was going to play in campus life and how it was going to meet students’ needs for academic resources.

The location of the library stirred controversy with Chatham’s neighbors. Residents on Murray Hill Avenue testified before Pittsburgh City Council that the building “means the destruction of the street” after it became clear that 10 houses would need to be razed to make space for the building, according to Chatham: A Transformational History.

The homes were destroyed despite neighbors’ objections. That conflict eventually led to the designation of Murray Hill Avenue as a City of Pittsburgh Historic District in 2000. Making the area a Historic District meant repairs, renovations, construction, and demolition on the street are more complex and heavily scrutinized before they are permitted.

The library opened in 1973, and it was “situated to leave one with the impression that it is the most important building on campus,” the Alumnae Recorder wrote. For the college, the building became a vital hub of intellectual life, resulting in a massive increase in stack and study areas, so the library could finally house the growing body of volumes.

On the inside, it featured groovy (if not entirely ergonomic) furniture and a color scheme of orange, purple, and green. But it does not seem that the three desired fireplaces ever made it into the final design.

Later documents give the sense that discussions over library resources in the 1980s were the same as those that were likely happening in libraries all over the world then. Records show that the college’s resources were increasingly put into digital technology and computers as they became more accessible and were used more by students.

It wasn’t until 2001 that the JKM Library went through a massive renovation that saw the changing of the old color scheme with a more neutral grey and cranberry. A new heating and cooling system, automatic front doors, and various other additions and upgrades were made throughout the building.

"The days of seeing the doors propped open to allow fresh air in are gone,” a reporter wrote in Communique in 2001. This renovation also saw an expanded computer lab as microfilm was moved to a multimedia room, where it sat alongside VCRs and periodicals.

Things are still changing occasionally; Tighe says the most significant development in recent years is the collapsable stacks in the basement, which allow the JKM to store valuable materials while conserving space.

Even more than 50 years after its construction, the precast concrete and glass building remains a hub on campus. Students can still find plenty of books in the JKM while also being able to access modern digital resources like ebooks and Kanopy film streaming.

And anyone who’s gone up to the third floor and peered out the north-facing windows knows that the library is still pretty “swelegant,” though they’d be hard pressed to find any smoking lounges.

Want to see our historic campus for yourself? Schedule a tour with our Admissions team, explore by yourself with our self-guided QR code tour, or take a virtual tour on your personal device wherever you are!

Mick Stinelli is a Writer and Digital Content Specialist at Chatham University. His writing has previously appeared in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and 90.5 WESA, and he has a B.A. in Broadcast Production and Media Management from Point Park University. Mick, a native of western Pennsylvania, spends his free time watching movies and playing music.