An Emoji Is Worth...What, Exactly?

It’s not every day that Vogue magazine wants to talk to a Chatham researcher, but Assistant Professor of Psychology Monica Riordan, PhD was ready. Dr. Riordan studies computer-mediated communication (such as texts, instant messaging, and emails), and she recently published a study in the Journal of Language and Social Psychology about emojis—the little pictures of everything from a thumbs-up to a salamander to the Romanian flag that we see on our phone screens and computer monitors.

Some people think that emojis grew out of emoticons, combinations of punctuation that help writers communicate the emotion behind a text or an email. The smile is a common one: :) In fact, many computer programs (including Microsoft Word) automatically replace emoticons with emojis: in the case of the colon + right parenthesis, it’s replaced with a smiley face.

“But if you look at all the 2000+ emojis that exist, only a small percentage of them are faces,” says Dr. Riordan. “The vast majority are objects. It begs the question, what are these non-face emojis for? What do they communicate?”

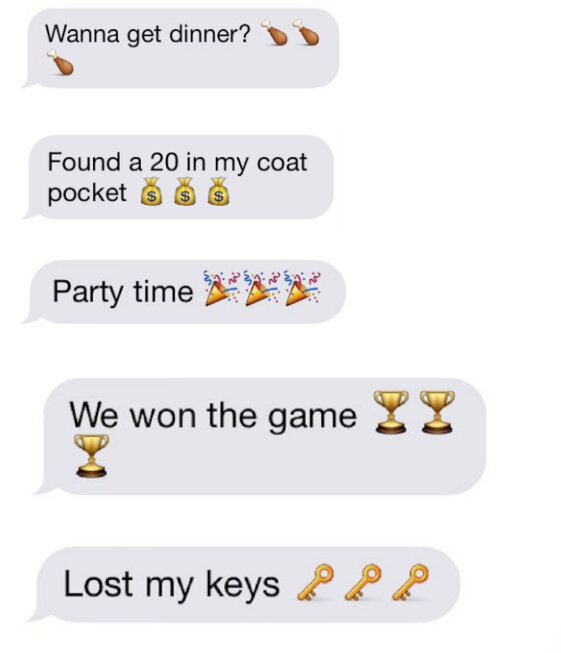

To investigate this question, Dr. Riordan worked with students to develop a set of texts that they could imagine receiving (“ecologically valid,” in psychology-speak), and paired the texts with zero, one, two or three emojis. She then showed the texts to study participants and asked them to rate how much of each of eight emotions (joy, trust, fear, surprise, anger, sadness, disgust, and anticipation) was present in the text message.

The results surprised her.

“It’s intuitive that if you use a smiley emoji, it will make you seem happier,” says Dr. Riordan. “But it’s not quite as intuitive that an emoji of a tree should suddenly make people seem happier, and yet they seem to. I was really surprised that of all eight emotions that I looked at, joy just significantly increased every single time.

"People just seem more joyful when they use emojis, no matter what that emoji is.”

Cara Gillotti, Senior Writer at Chatham University: Why do you think that might be?

MR: I think it adds an element of playfulness. If you’re really angry about something, you don’t play with language, right? You’re very terse, very to the point. Emojis are a form of art. They’re a form of playing with language.

CG: Do you think that's their main purpose?

MR: I think emojis are used in a few ways. For one, they might be used to disambiguate meaning. For example, if I send you a text that just says “Party time!”, that could mean a baby shower, a graduation party—you don’t know. But if I include an emoji of two beer glasses clinking, it tells you more about what kind of party it’s going to be. But of course the extent to which they do that depends on which emoji you use, for example, a balloon emoji may not differentiate.

I was working closely with a former student—who is now in the Quantitative Psychology PhD program at Notre Dame—and we spent many hours talking about what emojis mean. She showed me a text she got from a friend that said “See you later” with a unicorn emoji after it, and I was like “What does that mean?” It turns out that they had negotiated the meaning of the unicorn emoji to be a personality signature, like a hidden understanding, a shared joke just between the two of them. And I found that really interesting, and we put together this theory, that by having this hidden meaning inside joke emoji, you’re almost performing your role as a friend, saying “we’re besties."

The meaning of emojis is negotiated and changes over time. Emojis rise and fall in popularity, more emojis are made, and some emojis are deleted from the favorites list. In these ways, they are a lot like words, and have become a language unto themselves.

Emojis can also be great timesavers in terms of acting out social roles too. Let’s say you’re part of a sales team that just won an award. You could go down to the office and give everyone a high-five, or you could type a couple trophies, a couple of high fives, and text them to everybody, and you’re “present” in that moment.

And sometimes emojis have no meaning whatsoever, sometimes they’re just like rainbows and flowers and whatever else. I have nothing else to say so I’m just going to text you a bunch of emojis in a row.

CG: So we don’t always know what emojis mean.

MR: Nope. In fact, people who are older than college age tend to think of emojis as pictograms—that they represent the actual object. And this can lead to misunderstandings, because the people who use emojis more often actually consider them to be more like ideograms. Which means they don’t represent a trophy in reality, they represent the idea of being a champion, the idea of winning.

CG: How can we tell whether they're used as pictograms or ideograms?

MR: Apple recently came out with an upgrade to the iPhone that suggests emojis for words you type in a text— if you text “tree”, it will suggest replacing that word with an emoji of a tree. The problem is, most people don’t do this. The most common place for an emoji is at the end of a text, not in the middle, and rarely in place of words. They're used as punctuation.

CG: Interesting.

MR: Yeah. So, because emojis are often seen as ideograms, we can never really know what they mean. With some, there's almost like a cultural-level negotiation of their meaning. I thought it was really interesting that negotiation happens at the cultural level, and also at the interpersonal level, like with my former student and her best friend.

CG: I looked at one of the papers your studies references, and was intrigued by the finding that texts that end with periods are actually seen as being less sincere.

MR: One of my students told me that she uses a period to specifically end a conversation. When you’re face and face with someone, you walk away and the conversation ends. But conversations over text message can go on perpetually. Maybe there’s a delay, and 20 minutes later you get a message. It’s a constant, ongoing conversation. So she feels that if she wants to end the conversation, she puts a period there to show that we are now closing.

CG: So it’s a deliberate decision that she’s making?

MR: Exactly. And it’s so interesting to me that it’s using punctuation in a completely different way. It’s not ending a sentence; it’s ending a conversation.

CG: In your study, did you find that three emojis—trophies, for example—correlated with more joy than two trophies?

MR: No, interestingly—if we look at the trophy, joy went up almost an entire point from zero emojis to one emoji. But two emojis were basically the same as one emoji, and when you added a third, it went up only about another three-quarters of a point. So it looks like the important thing is whether an emoji is included, not the number of emojis. Only rarely did adding more emojis make an emotion more intense.

If you look online, you will find like the "laughing while crying" emoji three times in a row, and that’s supposed to indicate the intensity of the emotion. But in reality, most of the time we’re not really feeling the ways that we’re communicating that we’re feeling. It’s all a complete performance, so you’re performing the social role.

CG: Do people use emojis in emails?

MR: It is extremely infrequent. Most people – especially teenagers and 20-somethings don’t email their friends or family. To them, email is strictly something they use for professional correspondence.

CG: Are you thinking about extending this line of research?

MR: Yes, I am. So, if my father or mother sends me an eggplant emoji, I know they don’t mean certain associated meanings. But if a friend sends it, I think “she knows what that means!" I judge the meaning of the emoji based on the person who sends it. It’s obviously very complex, but I think I’d like to untangle some of the relationships between context and emoji use, and meaning of the emojis of that context.

Read Vogue’s coverage of the study here.

This study was funded by a Chatham faculty research grant. Chatham University’s undergraduate psychology program allows students to explore contemporary theory and research in psychology while thinking scientifically about behavior and mental processes, appreciating and respecting others and their differences, and to pursue a variety of career paths or graduate school.